Sustaining knowledge and investment in ecosystem services

Public Domain. Picture by Mariano, Own work 2005, via Wikimedia Commons

“Effective management of ecosystems is constrained both by the lack of knowledge and information about different aspects of ecosystems and by the failure to use adequately the information that does exist in support of management decisions.”

(Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, Summary for Decision-makers – MA 2005, p. 23)

Climate and Ecosystems – Stability and Crisis

The current climate crisis can be described as a severe instability of a huge and complex dynamic system – the Geosystem Climate. Stability allows a dynamic system to exist. It means the capacity to maintain the system status close to the point of equilibrium after a disturbance. So, stability is not about immobility.

A very specific kind of stability is cyclical stability, by which the system’s status changes along certain processes, but returns close to its original status. From the very beginning of human emancipation from the natural world, cyclical stability was observed as a matter of fact. Humans observed and became conscious of the night-day cycle, the lunar cycles, the cyclical appearance of stars in the night sky and the positioning of constellations, and of hot and cold periods, dry and wet periods, with winds blowing from different directions.

With this consciousness about cyclical stability, they also started to adapt their lifestyle to the different cyclical conditions better than other living species, and, led not only by instincts, they started to introduce some small changes in the world around them. They realised some changes would help them, and so they added further changes. But they were always still adapting to what they easily recognised as the immense world of which they were only a tiny part.

Humans could also see that their world was not all about cyclical order, but also about abrupt changes never experienced before, and therefore about disorder caused by geological, meteorological or biological events. These abrupt changes often only caused short term effects, so that the previous ordered status was soon reached again, at least on a wider scale, although locally the old ordered shapes could be lost forever.

Sometimes, abrupt changes would cause permanent effects, leading to migrations, when adaptation became impossible. But migrations were still based on the hope that the grand system Earth was still in place.

So cyclical patterns of the world, and therefore system stability, have always been deeply embedded in human consciousness. But this stability is first of all deeply rooted in the biological processes of all living kingdoms. From this perspective, for example, animal instincts are essentially basic routines, which regulate their lives. Without system stability, instincts can not work, and animal wildlife, as we know it, would come to an end.

The existential precondition of system stability is even more evident for plants since they grow but cannot move from the place where they germinated: they cannot run away for survival, as animals do as soon as they perceive danger.

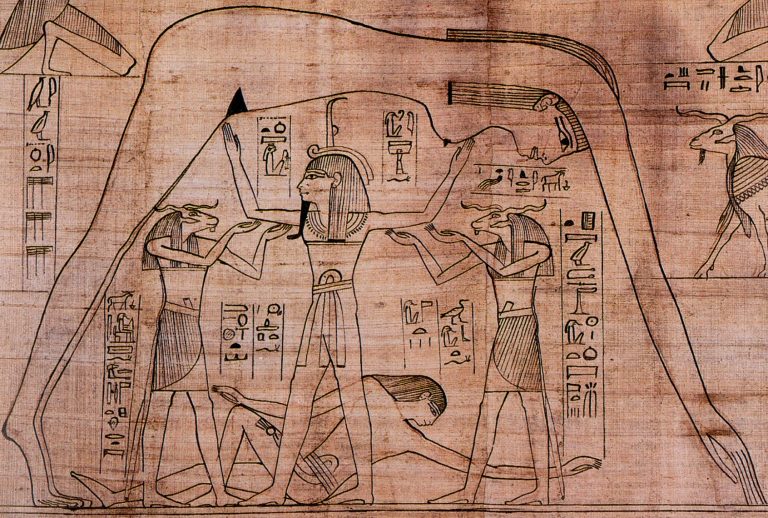

Detail from the Greenfield Papyrus, photo by the British Museum – What Life Was Like on the Banks of the Nile, edited by Denise Dersin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“The structure and functioning of the world’s ecosystems changed more rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century than at any time in human history.” (MA 2005, p. 2)

“nature is in a state of crisis. The five main direct drivers of biodiversity loss – changes in land and sea use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species – are making nature disappear quickly.” (EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, § 1)

“The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis are intrinsically linked. Climate change accelerates the destruction of the natural world through droughts, flooding and wildfires, while the loss and unsustainable use of nature are in turn key drivers of climate change. But just as the crises are linked, so are the solutions. Nature is a vital ally in the fight against climate change. Nature regulates the climate, and nature-based solutions, such as protecting and restoring wetlands, peatlands and coastal ecosystems, or sustainably managing marine areas, forests, grasslands and agricultural soils, will be essential for emission reduction and climate adaptation. Planting trees and deploying green infrastructure will help us to cool urban areas and mitigate the impact of natural disasters.” (EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, § 1)

Many natural systems are near the hard limits of their natural adaptation capacity and additional systems will reach limits with increasing global warming (high confidence).”

(IPCC, Climate Change 2022, Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 2022 – IPCC 2022, SPM.C.3.3)

Anthropisation

The Great Mother …

From the very beginning and over millennia, mother earth had been seen and understood as the only source of human survival: feeding, clothing, and providing them with a home.

Heraklion Archaeological Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

…. and the first agricultural revolution

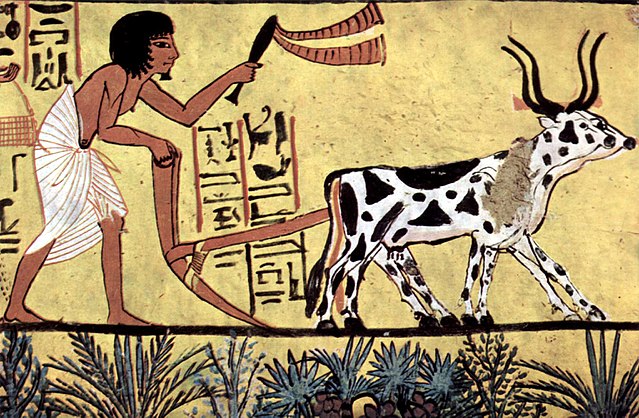

Starting in neolithic times, the adoption of agriculture allowed humans gradually to increase their food production, consumption and the accumulation of a surplus.

Painter of the burial chamber of Sennedjem, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Anthropisation – The age of self-referentiality

Millennia went by and finally, after a long gestation in the Middle Ages, a new anthropocentric consciousness came into being, initially fragile, but ready to grow to unseen heights.

Day by day – although the exploration of new lands and the discoveries of natural science enormously expanded human horizons – the world diminished in the eyes of the growing child: the only sun at the centre of the universe. The child grew and consciously killed his father, apparently against his heritage of faith and hope.

From inside its self-created bubble, humankind perceived all matter lying available to be shaped at will into commodities, and, unconsciously, the child started to kill mother earth. Only unconsciously, because, millennia before, in the Occident mother earth had already been pushed backstage behind masculine gods.

This was the evolution from those ages when humans perceived themselves only as a tiny part of Earth, to the present time in which they mostly see themselves as the only worthy creatures, with everything around them either commodities for pure exchange or worthless residue.

“With humans now consuming more resources than ever before, the current patterns of development across the world are not sustainable. […] One of the key elements for achieving sustainable development is the transition towards Sustainable Consumption and Production (SPC) […] SCP is about fulfilling the needs of all while using fewer resources, including energy and water, and producing less waste and pollution”.

“In Locke’s view, it was the investment of labor into the cultivation of natural resources which made them economically valuable, consequently making them the objects of proprietary rights. Leaving nature in an uncultivated state was, according to this view, almost a sin. […] Based on the ancient Roman principle of res nullius, or the similar notion of vacuum domicilium, this argument claimed that ‘empty things’, primarily land, belonged to all mankind till they were made use of […] Any notion of a tragedy of the commons, of the idea that nature was finite and its use therefore needed to be regulated, was totally foreign to this outlook”

(N. Wolloch, Before the Tragedy of the Commons, Early Modern Economic Considerations of the Public Use of Natural Resources, 2018, Theoretical Inquiries in Law, pp 413-414)

“Will mankind murder Mother Earth or will redeem her? He could murder her by misusing his increasing technological potency. Alternatively he could redeem her by overcoming the suicidal, aggressive greed that, in all living creatures, including Man himself, has been the price of the Great Mother’s gift of life. This is the enigmatic question which now confronts Man.”

(Arnold Toynbee, Mankind and Mother Earth, A Retrospect in 1973)

Carol Stoker NASA Ames Research Center, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Codrington, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Anthropisation – The time of scarcity and uncertainty for Global Commons

Mild temperatures, abundance of water and food or healthy living conditions: those things which appeared limitlessly given to affluent societies, now emerge for everyone as scarce and uncertain.

Limitless availability – the heritage of anthropocentric consciousness – has become the dominant mindset, together with the idea that technology and adaptation can overcome all physical constraints.

“Adaptation does not prevent all losses and damages, even with effective adaptation and before reaching soft and hard limits. Losses and damages are unequally distributed across systems, regions and sectors and are not comprehensively addressed by current financial, governance and institutional arrangements, particularly in vulnerable developing countries. With increasing global warming, losses and damages increase and become increasingly difficult to avoid.”

“In the space of a single lifetime, society Mankind itself suddenly confronted with a daunting complex of trade- offs between some of its most important activities and ideas. Recent trends raise disturbing questions about the extent to which today’s people may be living at the expense of their descendents, casting doubt upon the cherished goal that each successive generation will have greater prosperity. Technological innovation may temporarily mask a reduction in earth’s potential to sustain human activities; in the long run, however, it is unlikely to compensate for a massive depletion of such fundamental resources as productive land, fisheries, old- growth forests, and biodiversity”

“The last few decades have been a time of dynamic changes across the world […]. However, these achievements and changes have come at a significant cost to the environment. Increasing demand for energy, food, water and other resources has resulted in resource depletion, pollution, environmental degradation and climate change, pushing the earth towards its environmental limits.

Ocean Drover / Bahnfrend, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

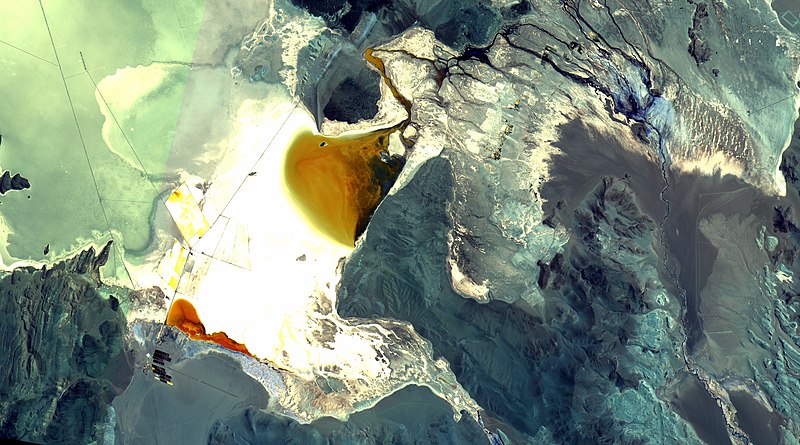

Salar del Hombre Muerto, Argentina / Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra/INPE, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

A chasm has opened between scientific knowledge about the consequences of anthropisation and the human behaviour producing these consequences.

The concept of “Ecosystem Services” is a major leap forward in the application of scientific knowledge to the environment.

Par Artiste inconnu — Stèle d’Ousirour, prêtre d’Amon à Thèbes Louvre Museum (détail), Mbzt (2013), CC BY-SA 3.0